The Donbas war began on April 7, 2014, when pro-Russian militants staged a coup in the eastern Ukrainian city of Donetsk. In the center of this industrial region, which was home to six million people speaking primarily Russian at the time, an armed conflict broke out between an expanding Russia and Ukraine seeking to solidify its independence. After 10 years of conflict, the Donbas have been reduced to a barren wasteland, with Russification imposed with force.

During the ten years of fighting in the Donbas, the names of numerous towns, including Bakhmut and Avdiivka, were included in international news reports, gaining widespread recognition outside of Ukraine. Together with the Azovstal steelworks in Mariupol and the Donetsk International Airport, these locations are currently in ruins.

Given the benefit of historical context, the Donbas battlegrounds seem to have served as a model for Russia’s massive military incursion into Ukraine.

Russia formally annexed Donetsk and Luhansk, the two administrative areas, or oblasts, that make up the Donbas region of Ukraine, in September 2022. They are now a part of the Russian Federation, Moscow claims. The bulk of the international world and the Ukrainians, who still hold some degree of authority over the region, believe that this annexation is unlawful.

The Donbas is still the site of brutal trench warfare, reminiscent of the Battle of Verdun a century after hostilities started. Military analysts estimate that whereas their Russian opponents can fire between 300,000 and 600,000 artillery shells each month, the Ukrainians can fire up to 60,000 artillery shells per month throughout the 1,000-kilometer front line.

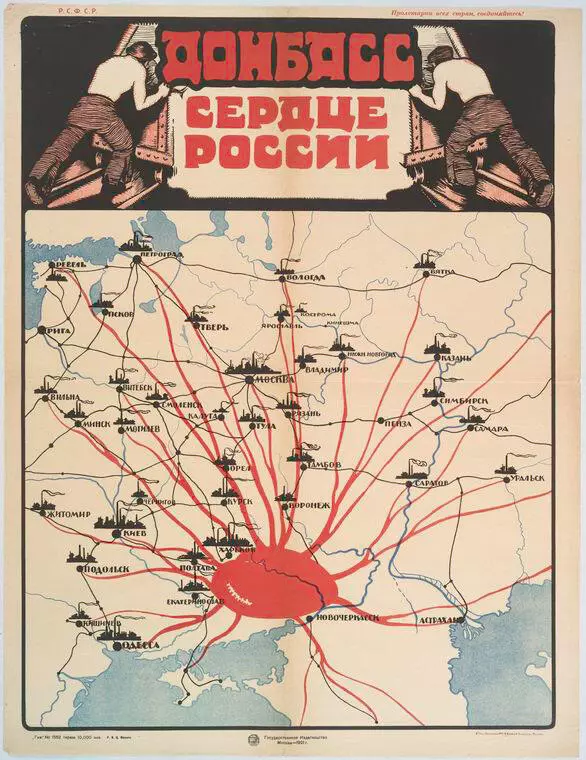

The protagonist in Soviet and Russian mythologies

The area has been a part of Ukraine since its independence in 1991 and is called after the Donets River and its mining basin, sometimes known as the Donets Basin. Greater in area than the Netherlands, the Donbas was first part of the USSR and subsequently the Russian Empire.

John Hughes, a Welshman, established a massive metallurgical complex of foundries and coal mines in 1869, which transformed the local economy and propelled Donetsk, the major city in the region, into the industrial era. The Donetsk basin supplied 68% of the coal used by the Russian Empire by 1900.

A third of the Donbas population, according to an imperial census conducted in 1897, were Russians drawn to the area by the growth of heavy industry and mining. The Tsarist government noted in the same census that half of the population was Ukrainian, with the remaining minority communities consisting of Jews, Tatars, Germans, and Greeks.

“Stalino” was the name of the town from 1924 to 1961. It was the setting for the adventures of Alekseï Stakhanov, a coal miner whose extraordinary output made him a Stalinist propaganda hero and a champion of Soviet productivity. Moscow saw the Donbas and its labor force as an industrial stronghold and an essential component of Russia during the Soviet era.

Historian Galia Ackerman says, “In the Soviet imagination, Donbas was the furnace of the entire Soviet Union.” As industrialization grew, a large number of highly qualified Russian engineers and laborers moved to the area. The 1930s saw a substantial Russification of the Donbas.”

Nonetheless, 83% of Donbas residents supported Ukrainian independence in the 1991 election. The largely Russian-speaking populace found it difficult to adjust to a post-communist society in the years that followed, which were characterized by deindustrialization and a dire economic catastrophe.

Over the next few decades, voters in Donbas and other eastern Ukrainian regions supported Russian-affiliated political parties in every presidential election held in that country.

In contrast to Yulia Tymoshenko’s pro-European party, Viktor Yanukovych’s Party of Regions received 80–90% of the vote in the 2010 elections.

According to Ackerman, the Donbas was “a blighted region where the population was impoverished and greatly missed the Soviet Union” just before the conflict started in 2014. “Several oligarchs and local mafias controlled most of the heavy industry. In certain communities, the boss was in charge of everything, including social services and healthcare.” Numerous reporters have noted that these local tycoons also maintained control over the media and did not accept criticism.

The Russian leadership thereafter, according to Goya and Lopez, “aimed at the partition of Ukraine,” after its attempts to conquer the entire nation were twice foiled: once in 2005 during the Orange Revolution and again in 2013–2014 during the Maidan Uprising.

“The Kremlin has no shortage of ideologues to theorize about the creation of a buffer state and to revive the old Tsarist term ‘New Russia,’” the historians write. The term “New Russia” refers to the areas of Ukraine “where Russian speakers are in a relative majority or significant minority,” which includes the provinces of Kherson, Odesa, Mikolayev, Luhansk, Donetsk, and Dniepropetrovsk.

The techniques Russia employed to take control and acquire land, which worked so well in Crimea, were once again implemented in April 2014, according to geographer and diplomat Michel Foucher. “The historical argument, the role of special forces, the use of violence, a false pretence of a referendum, all of this is replicated in the Donbas,” according to him. Two referendums were held in Donetsk and Luhansk on May 11, 2014; neither Ukraine nor any Western nation recognized the results of these polls. With overwhelming victories in both elections, the “yes” vote for independence from Ukraine resulted in the establishment of the Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) and the Luhansk People’s Republic (LPR).

War of proxy or separation?

Many in Ukraine accused Americans and Europeans of being cowardly in the face of Russian aggression in 2014. According to Kyiv, Moscow was leading the “pro-Russian separatists”; without Moscow’s encouragement and direct support, the separatists would never have taken up arms to defend their identity and language.

According to expert Aliyev, Russia’s extensive military participation in Ukraine began with the conflict that broke out in the Donbas. Russia kept a constant military presence, varying in strength based on the circumstances, in the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics until 2022. There was a higher deployment of regular military soldiers during times of acute confrontation with Ukraine. He clarifies that at other times, Russian military security services dispatched units to assist the local insurgents.

As the conflict progressed, local players with regional ambitions – such as Alexander Zakharchenko, the first leader of the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic – were eliminated. Considered insufficiently compliant by his Russian allies, Zakharchenko was assassinated in a 2018 car bomb attack. His counterpart in the Luhansk People’s Republic was replaced on Moscow’s orders. Since then, the two breakaway republics have been led by political figures who have pledged allegiance to the Kremlin.

“Between 2016 and 2022, these two entities became almost entirely dependent on the Russian Federation in every way: financially, economically, and militarily. Moscow paid salaries, pensions, and so on. It is probably from this period onwards that we can speak of Russia’s governance by proxy,” says Aliyev.

The second Donbas war and the nibbling away of Ukraine’s territory

On February 21, 2022, three days before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russia recognized the independence and sovereignty of the two self-proclaimed separatist republics of Donetsk and Luhansk. On February 24, Russian troops launched an all-out assault on Ukrainian territory, notably from Belarus, Crimea and Donbas.

In the first days of the war, Russian forces advanced across Ukraine, only to be halted by the Ukrainian army and territorial defense volunteers.

After the failure of the Russian advance toward Kyiv, followed by its withdrawal from the northeast of Ukraine at the end of March, Russia officially declared that the real aim of the “special operation”, as the Kremlin called it, was the “liberation of the Donbas”.

In a speech on February 24, Vladimir Putin claimed to want to disarm and “denazify” the whole of Ukraine.

- A Ukrainian press officer is seen trying to convince Valentyn, an 82-year-old local of Teterivske, to leave his home as Russian artillery began firing toward the village.

- Valentyn’s empty home. The elderly man died after his evacuation from Teterivske, passing away peacefully in the company of family members. His house is now being repaired.

The ‘New Russia’?

In the part of the Donbas that has been outside Ukrainian sovereignty for ten years, a return to the pre-2014 situation now seems highly unlikely. The breakaway Ukrainian republics that seceded in 2014 have since 2022 become official Russian territories, where the ruble circulates and a large proportion of the inhabitants have acquired Russian citizenship.

In March 2024, for the first time, the inhabitants of Donbas took part in a Russian presidential election, as did the inhabitants of other Ukrainian areas partially occupied by the Russian army such as Zaporizhzhia and Kherson, under strong pressure from the new authorities.

“Russification began in 2014. They changed the textbooks. They simply killed or imprisoned or drove away all those who were pro-Ukrainian. We mustn’t forget that there are nearly a million Donbas inhabitants who fled to Ukraine during the occupation of Donbas by pro-Russian and Russian forces,” Ackerman says.

Given the restricted access to this densely populated industrial region, it is difficult to accurately assess the destruction, reconstruction, and degree of Russification in the territories conquered by Russia.

In August 2022, Russian Deputy Prime Minister Marat Khusnullin presented Vladimir Putin with a plan to rebuild Mariupol within three years, including the redevelopment of the devastated Azovstal steelworks industrial zone, which was to be converted into a “technology hub”.

Since then, Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu has made a series of visits to the seaside city – not to mention the Russian president’s visit in March 2023 – to turn Mariupol into a showcase for the “New Russia” (“Novorossiya”).

Russian television frequently reports from Mariupol on the construction of brand-new apartment blocks, schools, and medical centers. “There’s a massive influx of Russians to Mariupol because it’s a city by the sea, and the sales pitch to Russians is ‘Come join us, real estate is cheap’. The town is being completely rebuilt, the incoming population replacing those that have left,” explains historian Ackerman.

Faced with Russian expansionism, European diplomacy seems to not influence at all the Russia-Ukraine war that has been raging for ten years on the fringes of Europe.

The 2014 and 2015 Minsk Agreements, supported by Germany and France, were a complete disaster.

“The military situation on the ground could lead to a kind of freeze around stable, well-defended front lines on both sides, without any agreed settlement or even ceasefire,” according to a February 2023 assessment made by French diplomat and geographer Michel Foucher.

How to draw the line between Russia and the EU after ten years of conflict in the Donbas will be a dilemma for diplomats in the years to come.

Reader Interactions